Chaining Five Business Logic Flaws to Steal $999,999

How an AI Pentester Found What Scanners Can't ... and most humans would miss

David Mound

Published on 2026-02-20 • 14 min readFive individually-reported vulnerabilities. Two low-privilege employee accounts. One fully autonomous AI. Zero human intervention.

Shinobi chained five separate business logic flaws in ShinoPay, a payment processing application with maker-checker controls, delegated approvals, and audit logging, into a complete financial fraud scenario. The result: $999,999 redirected to an offshore bank account, with the audit trail effectively hiding every step of the attack. The original $10,000 approval limit was bypassed by 100x.

No human researcher guided the attack. No pentester pointed Shinobi toward the delegation system or suggested trying post-approval amendments. Shinobi discovered each vulnerability independently, understood their business context, and then, like an experienced attacker, asked the question that matters: what happens when I combine them?

What is ShinoPay and why it matters

ShinoPay is a fintech platform used by enterprises to manage internal treasury operations and vendor payments. The name has been changed for this writeup, but the application, the vulnerabilities, and the attack chain are real. Shinobi tested it as part of a routine engagement.

The platform is built around the controls you'd expect from any serious payment system: role-based access control separating Users, Analysts, and Managers; a maker-checker approval workflow requiring one person to create a transfer and another to approve it; delegated approval authority with monetary limits; and an audit trail recording every action.

These are textbook financial controls. Banks, payment processors, and treasury systems rely on exactly this architecture to prevent fraud. The premise is simple: no single person should be able to create, approve, and settle a transfer on their own.

The premise is also wrong if the implementation has gaps.

The five vulnerabilities

Shinobi found seven vulnerabilities across ShinoPay during its assessment. Five of them, each individually concerning but arguably containable, turned out to be components of something far worse when combined. Here's what Shinobi found, and why each one mattered.

1. Unauthenticated GraphQL Reconnaissance

ShinoPay exposed a GraphQL endpoint at /query that required no authentication whatsoever. Anyone on the internet could query it. Shinobi did exactly that:

POST /query HTTP/2

Host: shinopay-lab.example.com

Content-Type: application/json

{"query":"{ delegations { id delegator_id delegate_id max_amount active } }"}

The response handed back the entire delegation map: who can approve on behalf of whom, and up to what amount. Delegation del-001 revealed that user usr-002 (an Admin) had delegated approval authority to user usr-004 (an Analyst named Mike) with a $10,000 limit.

This is the kind of information an attacker needs to plan a targeted fraud. Not just "there are delegations" but specifically which delegation to abuse and who to involve.

Why it seemed safe: The GraphQL endpoint was likely intended for internal tooling or a frontend that would add authentication at the application layer. The data itself (delegation relationships) might seem like organizational metadata rather than sensitive financial data.

Why it wasn't: In a payment system, the delegation map is the blueprint for bypassing controls. Knowing that Mike can approve up to $10,000 using the Admin's delegation is the difference between a speculative attack and a targeted one.

2. Mass Assignment in Transfer Amendments

ShinoPay's UI allowed users to amend pending transfers, changing the amount or description before approval. Reasonable functionality. But the API behind that UI accepted more parameters than the frontend ever sent.

Specifically, the /api/v1/transfers/{id}/amend endpoint accepted a beneficiary_id parameter that the UI never exposed. Shinobi discovered this by testing what the API would accept beyond the documented fields:

PATCH /api/v1/transfers/txn-231/amend HTTP/2

Authorization: Bearer $EMMA_TOKEN

Content-Type: application/json

{"beneficiary_id":"ben-230","description":"Office supplies quarterly payment"}

The transfer's destination silently changed from a legitimate vendor (ben-003, Office Supplies Ltd) to an attacker-controlled account (ben-230, Offshore Holdings LLC at Cayman National Bank). The description stayed the same. To anyone reviewing the transfer, nothing looked different.

Why it seemed safe: The UI only exposes amount and description fields. Frontend validation would prevent normal users from ever sending a beneficiary_id in an amendment request.

Why it wasn't: APIs don't have UIs. An attacker with a terminal and curl doesn't care what the frontend allows. The backend accepted and processed the parameter without question. A textbook mass assignment vulnerability, but with devastating implications in a payment context.

3. Cross-Scope Delegation Abuse

ShinoPay's approval system used delegations to let managers grant approval authority to subordinates. Delegation del-001 was clear: Admin (usr-002) delegates to Mike the Analyst (usr-004), allowing Mike to approve transfers up to $10,000 on the Admin's behalf.

The critical word is "on behalf of." The intended design is that Mike should only be able to use this delegation to approve transfers that the Admin would normally approve, transfers within the Admin's organizational scope.

Shinobi tested whether this scope was actually enforced:

POST /api/v1/transfers/txn-231/approve HTTP/2

Authorization: Bearer $MIKE_TOKEN

Content-Type: application/json

{"delegation_id":"del-001"}

It wasn't. Mike used the Admin's delegation to approve a transfer created by Emma (usr-005), a User in a completely different part of the organization. The approval endpoint checked that the delegation existed and was active, that Mike was the delegate, and that the amount was within the limit. It never checked whether the delegation's delegator had any relationship to the transfer or its requester.

Why it seemed safe: Delegations existed, had limits, and were tied to specific users. The system correctly prevented self-approval (Emma couldn't approve her own transfer). These are real controls that work in isolation.

Why it wasn't: The delegation validation was incomplete. It verified who can use the delegation but not what the delegation should be used for. In a system with dozens of delegations across departments, any delegate could effectively approve any transfer, collapsing the entire maker-checker model into a formality.

4. Post-Approval Amount Escalation

This is where the chain becomes extraordinary. After Mike approved Emma's $50 transfer using the Admin's $10,000 delegation, Emma went back and amended the already-approved transfer:

PATCH /api/v1/transfers/txn-231/amend HTTP/2

Authorization: Bearer $EMMA_TOKEN

Content-Type: application/json

{"amount":999999}

The amount changed from $50 to $999,999. The transfer remained in "approved" status. No re-approval was triggered. The $10,000 delegation limit was not re-validated. The transfer settled at the escalated amount.

Why it seemed safe: The amendment endpoint existed for a legitimate purpose: allowing corrections to pending transfers before approval. And the delegation limit was checked at approval time.

Why it wasn't: "Approved" should mean "locked." In any correctly implemented financial workflow, approval is a state transition that makes a record immutable (or at minimum, resets the approval if changes are made). ShinoPay treated "approved" as just another status field, not as a gate. The delegation limit was a point-in-time check, not an invariant.

5. Insufficient Audit Logging

The final vulnerability isn't an exploit. It's a cover-up. ShinoPay's audit trail recorded that amendments happened but not what changed:

{

"audit_trail": [

{"action": "transfer.created", "details": "Transfer created: USD 50.00 to Office Supplies Ltd"},

{"action": "transfer.amended", "details": "Transfer amended by emma.taylor@shinopay.internal"},

{"action": "transfer.approved", "details": "Transfer approved by mike.zhang@shinopay.internal (delegation: del-001)"},

{"action": "transfer.amended", "details": "Transfer amended by emma.taylor@shinopay.internal"}

]

}

An investigator reviewing this trail would see: a $50 transfer to Office Supplies Ltd was created, amended twice, and approved. No indication that the beneficiary was swapped to an offshore account. No indication that the amount was escalated 20,000x. Just "Transfer amended by emma.taylor," twice.

Why it seemed safe: The audit trail exists, captures the actor and action, and is timestamped. It looks like a functional audit log.

Why it wasn't: An audit log that records who did something but not what they changed is a liability, not a control. In a post-incident investigation, this log would actively mislead investigators. The original creation entry says "$50 to Office Supplies Ltd" and then two generic amendment entries. The final state of $999,999 to Offshore Holdings LLC is nowhere in the trail.

How the chain works

Each vulnerability above is individually a serious finding. But Shinobi didn't stop at individual findings. It recognized that these five flaws interact, that they form an attack path qualitatively different from any single vulnerability.

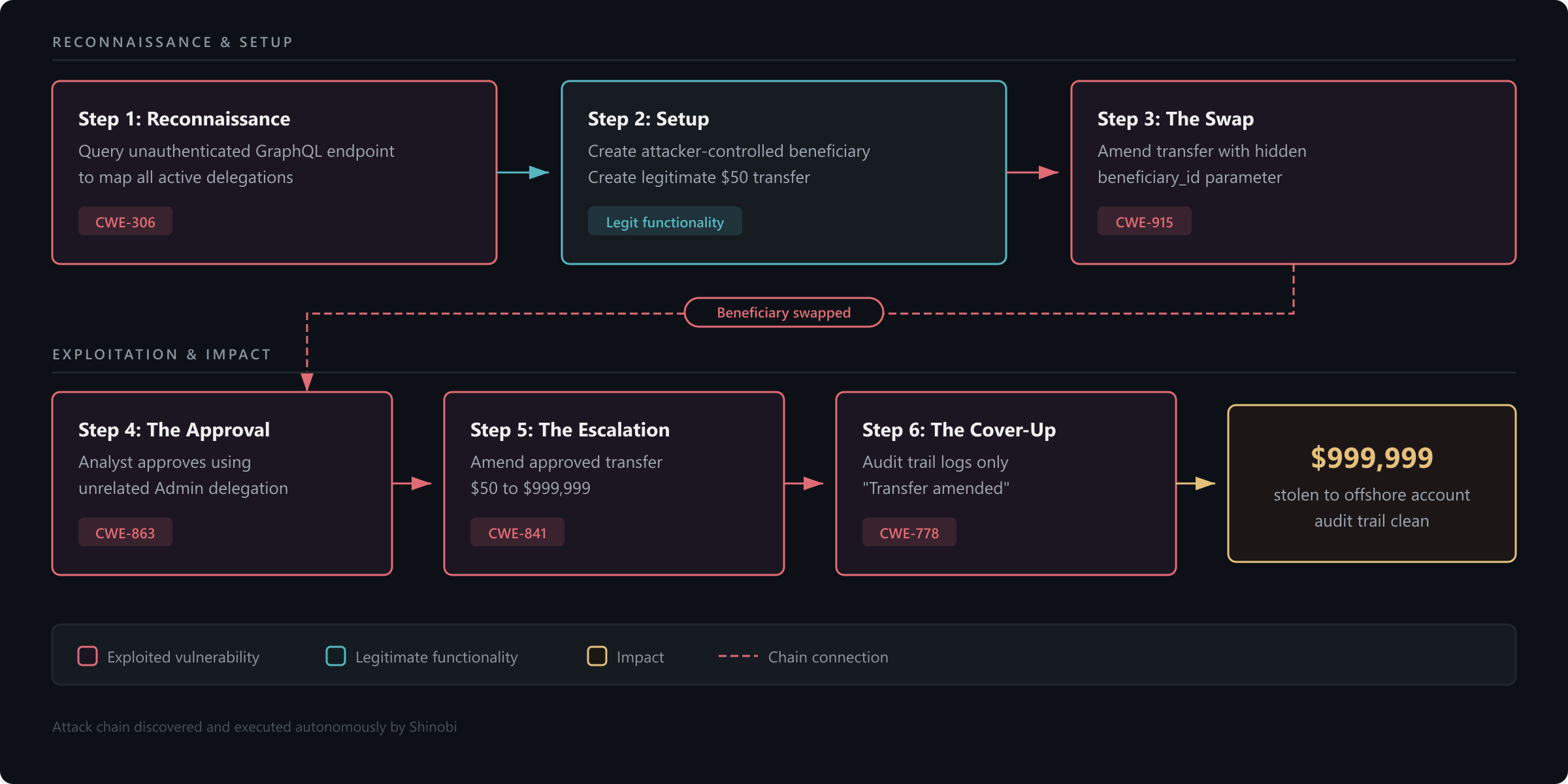

Here's the complete chain, as Shinobi constructed and executed it:

The attack chains five distinct vulnerability classes:

| Step | Vulnerability | CWE |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Reconnaissance | Unauthenticated GraphQL Access | CWE-306 |

| 3. The Swap | Mass Assignment in Transfer Amendment | CWE-915 |

| 4. The Approval | Cross-Scope Delegation Abuse | CWE-863 |

| 5. The Escalation | Post-Approval State Manipulation | CWE-841 |

| 6. The Cover-Up | Insufficient Audit Logging | CWE-778 |

Step 1: Reconnaissance. Query the unauthenticated GraphQL endpoint to discover all active delegations. Identify del-001: Admin delegates to Mike with a $10,000 limit. This intelligence tells the attackers exactly which delegation to abuse and who needs to be involved.

Step 2: Setup. Emma (User role) creates a beneficiary with attacker-controlled banking details: "Offshore Holdings LLC" at Cayman National Bank. She then creates a small, legitimate-looking transfer: $50 to Office Supplies Ltd, a real vendor. Nothing suspicious. A routine payment.

Step 3: The Swap. Emma amends the pending transfer, injecting the hidden beneficiary_id parameter to redirect funds from Office Supplies Ltd to Offshore Holdings LLC. The description stays the same. The amount stays the same. To anyone reviewing the queue, it's still a $50 office supplies payment.

Step 4: The Approval. Mike, the colluding Analyst or being socially engineered by Emma, approves the transfer using delegation del-001, the Admin's delegation, which has no organizational relationship to Emma or her transfer. The system checks the delegation limit ($10,000 > $50) and approves. Settlement begins.

Step 5: The Escalation. After approval, Emma amends the transfer one more time. She changes the amount from $50 to $999,999. The system accepts it. No re-approval is required. The delegation limit is not re-checked. The transfer settles at $999,999, 100x over the delegation limit, directed to an offshore bank account.

Step 6: The Cover-Up. The audit trail records "Transfer amended by emma.taylor@shinopay.internal" for each change. No before/after values. No field-level detail. An investigator sees a $50 office supplies payment that was amended twice and approved through proper channels.

The final state:

{

"id": "txn-231",

"beneficiary_id": "ben-230",

"amount": 999999,

"currency": "USD",

"description": "Office supplies quarterly payment",

"status": "approved",

"approver_id": "usr-004",

"delegation_id": "del-001"

}

$999,999 to Offshore Holdings LLC at Cayman National Bank. Description: "Office supplies quarterly payment." Approved through proper delegation channels. Audit trail clean.

Why existing controls didn't stop this

ShinoPay had real security controls. This wasn't an application with no guardrails. It had role-based access control, maker-checker workflows, delegation limits, and audit logging. Every one of those controls functioned correctly in isolation.

Role-based access control prevented Emma from approving her own transfers and restricted what each role could do. But it didn't prevent the mass assignment that enabled the beneficiary swap, because the authorization check confirmed Emma could amend her own transfers but didn't restrict which fields she could amend.

Maker-checker separation ensured two different people were involved in every transfer. Emma created it, Mike approved it. The control worked as designed. But it assumed that the transfer being approved was the same transfer that was created. With the beneficiary swap, it wasn't.

Delegation limits capped approval authority at $10,000 for Mike's delegation. The limit was correctly enforced at approval time. But the system never re-validated the limit after the post-approval amount escalation, because it never expected the amount to change after approval.

Audit logging captured every action. But without field-level change tracking, the log became a tool for concealment rather than investigation.

Each defense was architecturally sound. But attackers don't exploit individual controls, they exploit the seams between them. The mass assignment bypassed input validation. The delegation abuse bypassed organizational scoping. The post-approval amendment bypassed state management. The audit gap concealed it all. Together, they collapsed the entire financial control framework.

What makes this significant: Shinobi found all of this autonomously

Every step of this attack chain, from the initial GraphQL reconnaissance to the final post-approval escalation, was discovered, validated, and assembled by Shinobi without human guidance.

This matters because chained attacks are traditionally the domain of experienced human pentesters. Finding individual vulnerabilities is one thing. Understanding that a mass assignment vulnerability in a transfer amendment endpoint can be combined with a delegation scoping flaw and a post-approval state management gap to create a million-dollar fraud scenario ... that requires adversarial thinking. It requires understanding the business context of the application, not just its technical surface.

Consider what Shinobi had to understand to construct this chain:

Financial workflow semantics. Shinobi understood that transfers move through states (pending → approved → settled), that approval is a trust boundary, and that amendments after approval should be impossible. It tested this assumption and found it broken.

Organizational relationships. Shinobi understood that delegations represent hierarchical authority, that

del-001belonging tousr-002should only authorize approvals withinusr-002's organizational scope. It tested cross-scope usage and found no enforcement.Adversarial composition. Shinobi didn't just file five separate findings. It recognized that the GraphQL endpoint provides intelligence for targeting specific delegations, that mass assignment enables invisible beneficiary swaps, that delegation abuse enables colluding approval, that post-approval amendment enables limit bypass, and that the audit gap conceals all of it. Each finding enables or amplifies the others.

Anti-forensic awareness. Shinobi evaluated the audit trail not just as a vulnerability (insufficient logging) but as a feature of the attack, recognizing that the logging gap transforms the chain from a detectable fraud into a nearly invisible one.

This is the kind of reasoning that has historically separated automated scanners from human security researchers. Scanners find injection points. Researchers find business logic chains. Shinobi found both, and connected them.

Key takeaways

The gap between human pentesters and AI is closing fast. The conventional wisdom has been that automated tools find the easy stuff and humans find the business logic chains. This assessment challenges that assumption directly. Shinobi didn't just find injection points or missing headers. It understood financial workflows, organizational hierarchies, and state management semantics well enough to construct a multi-step fraud scenario that most junior pentesters would miss.

Vulnerability discovery is not enough. Attack composition is what matters. Standard automated testing finds individual vulnerabilities and reports them in isolation. Shinobi thinks differently. It looks at a collection of findings and asks: "How would an attacker actually use these together?" It's the difference between reporting five separate issues and demonstrating a million-dollar fraud. That shift, from vulnerability discovery to attack composition, is what has historically required a human adversarial mindset.

"Low risk" is a dangerous label. An unauthenticated GraphQL endpoint exposing metadata. A mass assignment bug. A missing state check. Individually, these might sit in a backlog for months, triaged as medium-severity issues that don't warrant immediate attention. Chained together, they enable the theft of $999,999 with a clean audit trail. Security programs that assess and prioritize findings in isolation will consistently underestimate their real-world exposure. Adversarial testing exists to show you what an attacker actually sees when they look at your vulnerability landscape.

Continuous adversarial testing isn't optional anymore. Human pentesters do this kind of work brilliantly, but they test quarterly or annually. The business logic flaws Shinobi found here aren't the kind that static analysis or traditional DAST scanners catch. They require contextual understanding of the application's purpose, its user roles, and its workflow invariants. That level of adversarial reasoning needs to run continuously, on every deployment, without waiting for the next engagement window.

Want to see how Shinobi finds and chains business logic flaws in your applications? Book a demo to experience autonomous adversarial testing in action.